TensorFlow Mechanics 101

Introduction

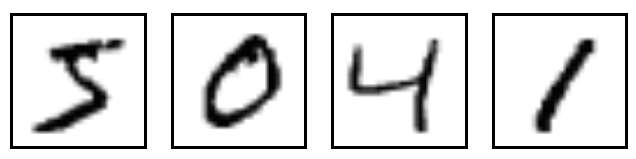

The goal of this tutorial is to show how to use TensorFlow to train and evaluate a simple feed-forward neural network for handwritten digit classification using the (classic) MNIST data set. The intended audience for this tutorial is experienced machine learning users interested in using TensorFlow.

These tutorials are not intended for teaching Machine Learning in general.

Please ensure you have followed the instructions to install TensorFlow.

This tutorial provides and in-depth explanation of the code within the mnist_fully_connected_feed example.

Simply source the minst_fully_connected_feed.R file to start training:

source("fully_connected_feed.R", echo = TRUE)Prepare the Data

MNIST is a classic problem in machine learning. The problem is to look at greyscale 28x28 pixel images of handwritten digits and determine which digit the image represents, for all the digits from zero to nine.

For more information, refer to Yann LeCun’s MNIST page or Chris Olah’s visualizations of MNIST.

Download

At the top of the run_training() function, the input_data$read_data_sets() function will ensure that the correct data has been downloaded to your local training folder and then unpack that data to return a named list of DataSet instances.

data_sets <- input_data$read_data_sets(FLAGS$train_dir, FLAGS$fake_data)NOTE: The fake_data flag is used for unit-testing purposes and may be safely ignored by the reader.

| Dataset | Purpose |

|---|---|

data_sets$train |

55000 images and labels, for primary training. |

data_sets$validation |

5000 images and labels, for iterative validation of training accuracy. |

data_sets$test |

10000 images and labels, for final testing of trained accuracy. |

Inputs and Placeholders

The placeholder_inputs() function creates two tf$placeholder ops that define the shape of the inputs, including the batch_size, to the rest of the graph and into which the actual training examples will be fed.

images <- tf$placeholder(tf$float32, shape(batch_size, IMAGE_PIXELS))

labels <- tf$placeholder(tf$int32, shape(batch_size))Further down, in the training loop, the full image and label datasets are sliced to fit the batch_size for each step, matched with these placeholder ops, and then passed into the sess$run() function using the feed_dict parameter.

Build the Graph

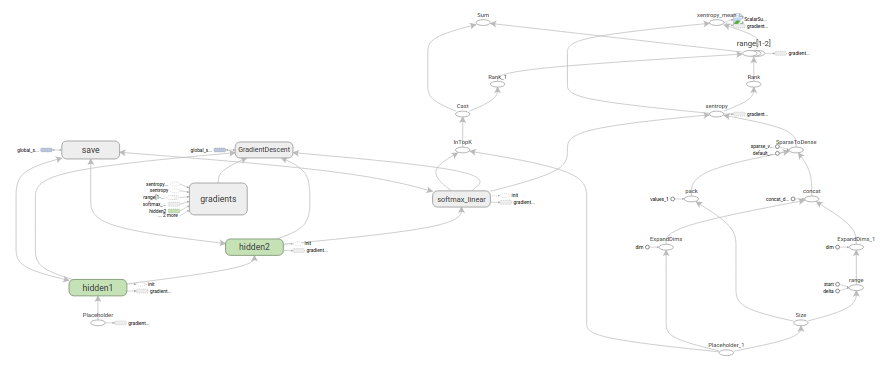

After creating placeholders for the data, the graph is built according to a 3-stage pattern: inference(), loss(), and training().

-

inference()- Builds the graph as far as is required for running the network forward to make predictions. -

loss()- Adds to the inference graph the ops required to generate loss. -

training()- Adds to the loss graph the ops required to compute and apply gradients.

Inference

The inference() function builds the graph as far as needed to return the tensor that would contain the output predictions.

It takes the images placeholder as input and builds on top of it a pair of fully connected layers with ReLu activation followed by a ten node linear layer specifying the output logits.

Each layer is created beneath a unique tf$name_scope that acts as a prefix to the items created within that scope.

with(tf$name_scope('hidden1'), {

# create layer

})Within the defined scope, the weights and biases to be used by each of these layers are generated into tf$Variable instances, with their desired shapes:

weights <- tf$Variable(

tf$truncated_normal(shape(IMAGE_PIXELS, hidden1_units),

stddev = 1.0 / sqrt(IMAGE_PIXELS)),

name = 'weights'

)

biases <- tf$Variable(tf$zeros(shape(hidden1_units), name = 'biases'))When, for instance, these are created under the hidden1 scope, the unique name given to the weights variable would be “hidden1/weights”.

Each variable is given initializer ops as part of their construction.

In this most common case, the weights are initialized with the tf$truncated_normal and given their shape of a 2-D tensor with the first dim representing the number of units in the layer from which the weights connect and the second dim representing the number of units in the layer to which the weights connect. For the first layer, named hidden1, the dimensions are shape(IMAGE_PIXELS, hidden1_units) because the weights are connecting the image inputs to the hidden1 layer. The tf$truncated_normal initializer generates a random distribution with a given mean and standard deviation.

Then the biases are initialized with tf$zeros to ensure they start with all zero values, and their shape is simply the number of units in the layer to which they connect.

The graph’s three primary ops – two tf$nn$relu ops wrapping tf$matmul for the hidden layers and one extra tf$matmul for the logits – are then created, each in turn, with separate tf$Variable instances connected to each of the input placeholders or the output tensors of the previous layer.

hidden1 <- tf$nn$relu(tf$matmul(images, weights) + biases)hidden2 <- tf$nn$relu(tf$matmul(hidden1, weights) + biases)logits <- tf$matmul(hidden2, weights) + biasesFinally, the logits tensor that will contain the output is returned.

Loss

The loss() function further builds the graph by adding the required loss ops.

First, the values from the labels_placeholder are converted to 64-bit integers. Then, a tf$nn$sparse_softmax_cross_entropy_with_logits op is added to automatically produce 1-hot labels from the labels_placeholder and compare the output logits from the inference() function with those 1-hot labels.

labels <- tf$to_int64(labels)

cross_entropy <- tf$nn$sparse_softmax_cross_entropy_with_logits(

logits = logits, labels = labels, name = 'xentropy')It then uses tf.reduce_mean to average the cross entropy values across the batch dimension (the first dimension) as the total loss.

tf$reduce_mean(cross_entropy, name = 'xentropy_mean')And the tensor that will then contain the loss value is returned.

Note: Cross-entropy is an idea from information theory that allows us to describe how bad it is to believe the predictions of the neural network, given what is actually true. For more information, read the blog post Visual Information Theory (http://colah.github.io/posts/2015-09-Visual-Information/)

Training

The training() function adds the operations needed to minimize the loss via Gradient Descent.

Firstly, it takes the loss tensor from the loss() function and hands it to a tf$summary$scalar, an op for generating summary values into the events file when used with a tf$summary$FileWriter (see below). In this case, it will emit the snapshot value of the loss every time the summaries are written out.

tf$summary$scalar(loss$op$name, loss)Next, we instantiate a tf$train$GradientDescentOptimizer responsible for applying gradients with the requested learning rate.

optimizer <- tf$train$GradientDescentOptimizer(learning_rate)We then generate a single variable to contain a counter for the global training step and the minimize() op is used to both update the trainable weights in the system and increment the global step. This op is, by convention, known as the train_op and is what must be run by a TensorFlow session in order to induce one full step of training (see below).

global_step <- tf$Variable(0L, name = 'global_step', trainable = FALSE)

optimizer$minimize(loss, global_step = global_step)Train the Model

Once the graph is built, it can be iteratively trained and evaluated in a loop controlled by the user code in fully_connected_feed.R.

The Graph

At the top of the run_training() function is a with statement that indicates all of the built ops are to be associated with the default global tf$Graph instance.

with(tf$Graph()$as_default(), {

# build graph

})A tf$Graph is a collection of ops that may be executed together as a group. Most TensorFlow uses will only need to rely on the single default graph.

More complicated uses with multiple graphs are possible, but beyond the scope of this simple tutorial.

The Session

Once all of the build preparation has been completed and all of the necessary ops generated, a tf$Session is created for running the graph.

sess <- tf$Session()Alternately, a Session may be generated into a with block for scoping:

with(tf$Session() %as% sess, {

# train, etc.

})The empty parameter to session indicates that this code will attach to (or create if not yet created) the default local session.

Immediately after creating the session, all of the tf$Variable instances are initialized by calling sess$run() on their initialization op.

init <- tf$global_variables_initializer()

sess$run(init)The sess.run() method will run the complete subset of the graph that corresponds to the op(s) passed as parameters. In this first call, the init op is a tf$group that contains only the initializers for the variables. None of the rest of the graph is run here; that happens in the training loop below.

Train Loop

After initializing the variables with the session, training may begin.

The user code controls the training per step, and the simplest loop that can do useful training is:

for (step in 1:FLAGS$max_steps) {

sess$run(train_op)

}However, this tutorial is slightly more complicated in that it must also slice up the input data for each step to match the previously generated placeholders.

Feed the Graph

For each step, the code will generate a feed dictionary that will contain the set of examples on which to train for the step, keyed by the placeholder ops they represent.

In the fill_feed_dict() function, the given DataSet is queried for its next batch_size set of images and labels, and tensors matching the placeholders are filled containing the next images and labels.

batch <- data_set$next_batch(FLAGS$batch_size, FLAGS$fake_data)

images_feed <- batch[[1]]

labels_feed <- batch[[2]]A dictionary is then generated with the placeholders as keys and the representative feed tensors as values.

dict(

images_pl = images_feed,

labels_pl = labels_feed

)This is passed into the sess$run() function’s feed_dict parameter to provide the input examples for this step of training.

Check the Status

The code specifies two values to fetch in its run call: train_op and loss.

for (step in 1:FLAGS$max_steps) {

feed_dict <- fill_feed_dict(data_sets$train,

placeholders$images,

placeholders$labels)

values <- sess$run(list(train_op, loss), feed_dict = feed_dict)

loss_value <- values[[2]]

}Because there are two values to fetch, sess$run() returns a list with two items. Each Tensor in the list of values to fetch corresponds to an array in the returned tuple, filled with the value of that tensor during this step of training. Since train_op is an Operation with no output value, the corresponding element in the returned list is NULL and, thus, discarded. However, the value of the loss tensor may become NaN if the model diverges during training, so we capture this value for logging.

Assuming that the training runs fine without NaNs, the training loop also prints a simple status text every 100 steps to let the user know the state of training.

if (step %% 100 == 0) {

# Print status to stdout.

cat(sprintf('Step %d: loss = %.2f (%.3f sec)\n',

step, loss_value, duration))

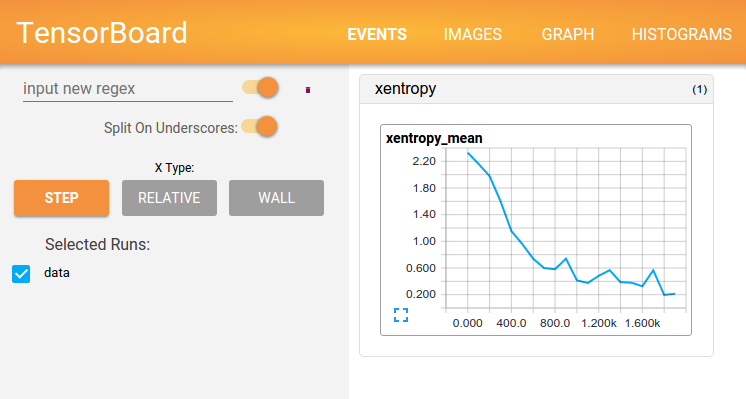

}Visualize the Status

In order to emit the events files used by TensorBoard, all of the summaries (in this case, only one) are collected into a single Tensor during the graph building phase.

summary < tf$summary$merge_all()And then after the session is created, a tf$summary$FileWriter may be instantiated to write the events files, which contain both the graph itself and the values of the summaries.

summary_writer <- tf$summary$FileWriter(FLAGS$train_dir, sess$graph)Lastly, the events file will be updated with new summary values every time the summary is evaluated and the output passed to the writer’s add_summary() function.

summary_str <- sess$run(summary, feed_dict=feed_dict)

summary_writer$add_summary(summary_str, step)When the events files are written, TensorBoard may be run against the training folder to display the values from the summaries.

NOTE: For more info about how to build and run Tensorboard, please see the accompanying tutorial Tensorboard: Visualizing Your Training.

Save a Checkpoint

In order to emit a checkpoint file that may be used to later restore a model for further training or evaluation, we instantiate a tf$train$Saver.

saver <- tf$train$Saver()In the training loop, the saver$save() method will periodically be called to write a checkpoint file to the training directory with the current values of all the trainable variables.

saver$save(sess, checkpoint_file, global_step=step)At some later point in the future, training might be resumed by using the saver$restore() method to reload the model parameters.

saver$restore(sess, FLAGS$train_dir)Evaluate the Model

Every thousand steps, the code will attempt to evaluate the model against both the training and test datasets. The do_eval() function is called thrice, for the training, validation, and test datasets.

# Evaluate against the training set.

cat('Training Data Eval:\n')

do_eval(sess,

eval_correct,

placeholders$images,

placeholders$labels,

data_sets$train)

# Evaluate against the validation set.

cat('Validation Data Eval:\n')

do_eval(sess,

eval_correct,

placeholders$images,

placeholders$labels,

data_sets$validation)

# Evaluate against the test set.

cat('Test Data Eval:\n')

do_eval(sess,

eval_correct,

placeholders$images,

placeholders$labels,

data_sets$test)Note that more complicated usage would usually sequester the

data_sets$testto only be checked after significant amounts of hyperparameter tuning. For the sake of a simple little MNIST problem, however, we evaluate against all of the data.

Build the Eval Graph

Before entering the training loop, the Eval op should have been built by calling the evaluation() function with the same logits/labels parameters as the loss() function.

eval_correct <- evaluation(logits, placeholders$labels)The evaluation() function simply generates a tf$nn$in_top_k op that can automatically score each model output as correct if the true label can be found in the K most-likely predictions. In this case, we set the value of K to 1 to only consider a prediction correct if it is for the true label.

correct <- tf$nn$in_top_k(logits, labels, 1L)Eval Output

One can then create a loop for filling a feed_dict and calling sess$run() against the eval_correct op to evaluate the model on the given dataset.

for (step in 1:steps_per_epoch) {

feed_dict <- fill_feed_dict(data_set,

images_placeholder,

labels_placeholder)

true_count <- true_count + sess$run(eval_correct, feed_dict=feed_dict)

}The true_count variable simply accumulates all of the predictions that the in_top_k op has determined to be correct. From there, the precision may be calculated from simply dividing by the total number of examples.

precision <- true_count / num_examples

cat(sprintf(' Num examples: %d Num correct: %d Precision @ 1: %0.04f\n',

num_examples, true_count, precision))